What is mitral valve regurgitation (MR)?

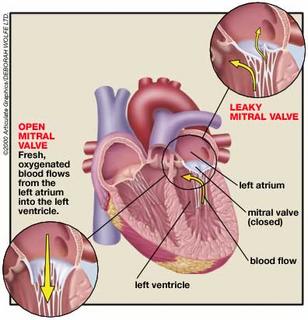

The mitral valve is similar to a one-way gate in the left side of your heart. Normally, the valve only allows blood to flow from the upper to lower heart chamber. But if the valve becomes diseased or injured so it cannot close properly, blood can leak backward (regurgitate) into the upper chamber (left atrium). This uncirculated blood causes the heart to work harder to pump the extra regurgitated blood (volume overload).

Mild cases of mitral valve regurgitation cause few problems, but more severe cases eventually weaken the heart and lead to heart failure.

See an illustration of the heart with its chambers and blood flow.

What causes mitral valve regurgitation?

There are two forms of mitral valve regurgitation: chronic and acute.

Chronic mitral valve regurgitation, the most common type, develops slowly over several years. The most common cause is mitral valve prolapse, in which the mitral valve flaps bulge the wrong way against the flow of blood, don't seal properly, and allow blood to leak backward. Other causes include heart failure, rheumatic fever, which can scar the heart valves, preventing them from closing completely; calcification of the tough ring of tissue (annulus) to which the mitral valve flaps are attached; congenital heart disease; and other heart problems.

Acute mitral valve regurgitation develops quickly and can be life-threatening. It occurs when the mitral valve or one of its supporting structures ruptures suddenly, creating an immediate overload of blood volume and blood pressure in the left side of the heart. Unlike chronic MR, your heart doesn't have time to compensate for the increased volume and pressure of blood. If not treated, acute MR can be fatal. Common causes of acute MR are heart attack and heart infection.

What are the symptoms?

If you have mild-to-moderate chronic mitral valve regurgitation, you may never develop symptoms. If you have moderate-to-severe disease, you may not have symptoms for decades. Depending on the severity of your mitral valve regurgitation and condition of your heart, you may not develop symptoms of heart failure until you're in your 40s, 50s, or 60s. Symptoms include shortness of breath with exertion, which later develops into shortness of breath at rest and at night; fatigue and weakness; and fluid buildup (edema) in the legs and feet.

With acute mitral valve regurgitation, you will be critically ill. Symptoms develop rapidly and include severe shortness of breath at rest, coughing, and rapid heartbeat.

How is mitral valve regurgitation diagnosed?

Most cases of mitral valve regurgitation are chronic and are diagnosed during a regular doctor's office visit. Acute mitral valve regurgitation is life-threatening and is usually diagnosed in the emergency room or while you are hospitalized.

Because you may not have symptoms with chronic mitral valve regurgitation, a specific type of heart murmur may be the first sign your doctor notices. Further tests will be needed to evaluate your heart and the severity of the regurgitation. Tests may include:

Various types of echocardiogram, a type of ultrasound to determine the severity of MR.

An electrocardiogram (EKG, ECG), to evaluate abnormal heart rhythms.

A chest X-ray, to evaluate heart size.

Cardiac catheterization, to determine the severity of MR and to look for coronary artery disease.

Tests for acute mitral valve regurgitation may include one or more of those used for chronic MR as well as a transesophageal echocardiogram, in which a device that sends sound waves is passed down the esophagus to take clearer images of the heart.

How is it treated?

Treatment for chronic mitral valve regurgitation includes monitoring your heart function and symptoms, preventing infection, and treating complications as they develop. Your doctor may prescribe medications, including: Vasodilators to help widen blood vessels and help the heart pump more efficiently.

Anticoagulants, such as warfarin (Coumadin), to prevent blood clots if you also have atrial fibrillation. Beta-blockers, or antiarrhythmics to control heart rate.

Antibiotics to prevent infections.

You may need surgery to repair or replace your mitral valve if the regurgitation becomes severe, if the size of your left ventricle (your heart's main pumping chamber) increases, or if your heart weakens. Mitral valve repair is preferred over replacement.

Treatment for acute mitral valve regurgitation occurs while you are hospitalized or in the emergency room. Because heart failure usually occurs with acute MR, vasodilators are given intravenously. Immediate surgery to repair or replace the valve will be necessary.

2 comments:

Lori and I have really been enjoying your thoughts. Just finished reading "Dear Max" and have a couple of things to add on and a couple of new thoughts.

#2. Change butt to ass when Max is 18

#7. Two of your teams are wrong. Change the Giants to the Broncos and the Knicks to the Nuggets. The Yankees can stay.

#19. Add: Save at least 10% of what you earn.

# 31. Add: unless it's a ballgame.

# 38 Add: and old people.

# 42 Add: When it is finished throw away the octopus and eat the cork.

Add...Real boys/men cry.

... Ask for directions.

I'm sure I can come up with others, just give me time.

Norm (Opa)

This is a great post on Mitral Valve Prolapse in every day life. I have Mitral Valve Prolapse and had it treated at Heathworx in Miami. Luckily they offered onsite counseling to help assure me I wasn't going nuts from the symptoms. Great post and keep it up.

Post a Comment