The more we learn about how the mind and body work the more we realize that there is a direct correlation between each of their states. The article below in this week's Newsweek discuss the connection between helathy hearts and positive mental attitudes and outlooks.

Mediation, Cognitive Therapy, Biofeedback are just some of the means of mending your heart with your mind. If that doesn't work, watch a couple of episodes of COPS and no matter what is going on in your life you'll know it could be worse.

************************

The Good Heart

Diet and exercise are not the whole secret to cardiovascular health. Mounting evidence suggests that your psychological outlook is just as important.

By Anne Underwood

Newsweek

Oct. 3, 2005 issue - You can call it the Northridge Effect, after the powerful earthquake that struck near Los Angeles at 4:30 on a January morning in 1994. Within an hour, and for the rest of the day, medics responding to people crushed or trapped inside buildings faced a second wave of deaths from heart attacks among people who had survived the tremor unscathed. In the months that followed, researchers at two universities examined coroners' records from Los Angeles County and found an astonishing jump in cardiovascular deaths, from 15.6 on an average day to 51 on the day of the quake itself. Most of these people turned out to have a history of coronary disease, or risk factors such as high blood pressure. But those who died were not involved in rescue efforts or trying to dig themselves out of the rubble. Why did they die? In the understated language of The New England Journal of Medicine, "emotional stress may precipitate cardiac events in people who are predisposed to such events." To put it simply, they were scared to death.

Folk medicine has always recognized that a sudden fright or bad news can be fatal. And the same Greek word, meaning "constriction," is the root of both "anger" and "angina." But the Northridge study—and others involving survivors of the 1981 Athens earthquake and the 1991 Iraqi Scud-missile attacks on Israel—helped fuel new research in what might be called psychocardiology, the profound connections between emotions and the cardiovascular system. For a long time, cardiologists resisted the idea that the heart, the sturdy wellspring of life, can be fatally deranged by a mental event. But it's not just sudden shocks like earthquakes that kill. Mounting evidence suggests that chronic emotional states such as stress, anxiety, hostility and depression take a far greater toll. "Fifty percent of people who have heart attacks do not have high cholesterol," points out Edward Suarez, associate professor of psychiatry and human behavior at Duke. The risk of psychological and social factors are almost as great as obesity, smoking and hypertension, the traditional medical markers for cardiovascular disease—which afflicts 70 million Americans and is the nation's No. 1 killer. Researchers are now starting to learn why. And a growing number of clinics are putting that insight to work in programs that tackle heart disease at one of its most unlikely sources: in the mind.

Our understanding has proceeded from the anecdotal to the epidemiological to the search for underlying mechanisms. As a critical-care nurse at Mad River Community Hospital in northern California in the 1980s, Debra Moser saw repeatedly how patients' attitudes seemed to affect the course of their heart disease. She was struck by one case involving a man in his 50s with an uncomplicated heart attack. He should have been out of the hospital within two or three days, but he lingered for six. "It was the first time I appreciated the power of negative thinking," says Moser. "He was very depressed, which is not unusual after a heart attack. But he obsessed over everything. He was hypervigilant about his case. It seemed to us that he worried himself into episodes of recurrent ischemia and chest pain." The chest pain wasn't just in his mind; tests showed reduced blood flow to the heart. Within a year, he suffered another heart attack and died.

Years later, Moser, now a professor of nursing at the University of Kentucky in Lexington, sought to quantify the effects she observed in that patient. At a meeting of the American Heart Association last fall she presented the results of a trial involving 536 heart-attack patients. She had measured their anxiety levels with a standard multiple-choice psychological test, and kept track of whether they had further complications—such as a second heart attack—while in the hospital. Those who scored the highest for anxiety on the psychological tests were four times more likely to suffer complications than those with the lowest scores. The lesson was clear: "Every day we take patients' blood pressure and listen to their heart," she says, "but we rarely do a systematic assessment of their psychological state, even though anxiety and depression are major risk factors."

In fact, doctors are finding that psychosocial factors pose far greater risks than they previously realized. Take depression. It at least doubles an otherwise healthy person's heart-attack risk, says Dr. Michael Frenneaux, professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Birmingham in England. And for people who have suffered a heart attack in the past, depression quadruples or even quintuples the risk of a second one. Hostility is an increasingly important risk factor, too. High hostility levels, as measured by a standard test, increased the chances of dying from heart disease by 29 percent in a large study of patients at Duke—and by more than 50 percent in people 60 and younger.

Even childhood trauma seems to have an impact on heart disease later in life. In a recent survey of more than 17,000 adults in San Diego, Dr. Maxia Dong at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that heart-attack risk went up by 30 to 70 percent in people who reported adverse childhood experiences, such as physical, sexual or emotional abuse, domestic violence or having family members who abused drugs or alcohol. The one reassuring note: parental separation or divorce, alone among the 10 variables studied, had no statistical effect on the risk of future heart attacks.

And if stress in childhood can lead to heart disease, what about current stress-ors—longer work hours, threats of layoffs, collapsing pension funds? A study last year in The Lancet examined more than 11,000 heart-attack sufferers from 52 countries and found that in the year before their heart attacks, patients had been under significantly more strains—from work, family, financial troubles, depression and other causes—than some 13,000 healthy control subjects. "Each of these factors individually was associated with increased risk," says Dr. Salim Yusuf, professor of medicine at Canada's McMaster University and senior investigator on the study. "Together, they accounted for 30 percent of overall heart-attack risk." But people respond differently to high-pressure work situations. The key to whether it produces a coronary seems to be whether you have a sense of control over life, or live at the mercy of circumstances and superiors.

That was the experience of John O'Connell, a Rockford, Ill., laboratory manager who suffered his first heart attack in 1996, at the age of 56. In the two years before, his mother and two of his children had suffered serious illnesses, and his job had been changed in a reorganization. "My life seemed completely out of control," he says. "I had no idea where I would end up." He ended up on a gurney with a clot blocking his left anterior descending artery—the classic "widowmaker." Two months later he had triple bypass surgery. A second heart attack when he was 58 left his cardiologist shaking his head. There's nothing more we can do for you, doctors told him.

Why do these stressors have such a potent effect? On the most obvious level, emotional states affect behavior. Depressed, angry people are less likely to stick with diet and exercise regimens and are more likely to smoke. In one study, the most hostile subjects consumed 600 more daily calories than the least hostile.

But behavior is only the beginning. Negative emotions can have direct effects, too, by provoking the stress response of the classic fight-or-flight mechanism. The body releases stress hormones, such as cortisol and epinephrine (adrenaline). In response, blood pressure and blood-glucose levels increase, while chemical changes in the blood enhance the clotting reaction to help heal wounds. In the short term, these are survival mechanisms. But over the long haul, chronic high blood pressure and elevated glucose damage blood vessels.

Current research focuses on the effects of inflammation. "Hostile and depressed people respond to the world in a chemically different way," says Suarez. They interpret more situations as stressful, provoking the release of more stress hormones. The immune system responds by ratcheting up inflammation, which promotes heart disease at every stage—from plaque formation to heart attack. In a 2004 study, Suarez found that people who score high on tests for anger, hostility or depression have higher blood levels of an inflammatory marker called C-reactive protein, which is strongly correlated with cardiovascular risk. "In those who were positive for all three traits, CRP levels were twice as high," he says. Similarly, Amy Ferketich at Ohio State University tested the blood of depressed versus nondepressed heart-failure patients—and found the depressed had nearly twice the levels of an inflammatory compound called TNF-alpha.

Inflammation aside, it's now clear that adrenaline itself can wreak havoc on the heart. Dr. Ilan Wittstein of Johns Hopkins recently identified a condition called stress cardiomyopathy, or "broken-heart syndrome," which looks on the surface a lot like a heart attack. Wittstein's patients had all experienced major shocks—the sudden death of a parent or child, a car accident, an armed robbery, even a surprise birthday party—and their hearts' ability to pump had suddenly weakened. Their symptoms mimicked those of a heart attack. Even their EKGs read like those of heart-attack patients. Yet these people showed no sign of blockage in their coronary arteries and very little of the blood-chemistry markers of heart-tissue death. And unlike heart-attack survivors, who take months to recover, these folks were usually fine within 72 hours. What was going on in their chests? Although there's still debate about the exact mechanism, Wittstein notes that the patients' blood levels of adrenaline were 30 times higher than normal, four to five times higher even than in patients undergoing an actual heart attack. He suspects this huge dose of a powerful hormone disrupts the way heart cells take up calcium, which is essential for heart-muscle cells to contract.

If negative or stressful emotions contribute to heart disease, could their opposites represent an avenue for treatment or prevention? Consider what happened when University of Utah psychologist Timothy Smith assigned 82 college students a task designed to cause stress. They had to argue either for or against a controversial topic, like raising the Social Security retirement age. Their responses, they were told, would be graded for clarity, organization and persuasiveness—and would be recorded on videotape. But first, they were asked to write a few paragraphs about either a close, supportive friend or a casual acquaintance. During the subsequent filming, says Smith, "Heart rate and blood pressure went up a lot. But they went up less when people spent a minute or two beforehand thinking of someone who mattered to them." Over a period of years, the effects of having such supportive friends—and appreciating them—would be cumulative.

Optimism seems to have similar benefits, and may even help slow the progression of atherosclerosis. Psychologist Karen Matthews at the University of Pittsburgh observed 209 healthy, postmenopausal women for three years and found that the most optimistic ones had very little thickening in their carotid arteries—just 1 percent, versus as much as 6.5 percent in the pessimists.

Even laughter is starting to look like a cardiac elixir. In one recent study, Dr. Michael Miller of the University of Maryland School of Medicine found that watching a funny movie for 15 minutes relaxed people's peripheral arteries and increased blood flow for as long as 45 minutes afterward—comparable to the effect of aerobic exercise. He now recommends 15 minutes of hearty laughter daily—chuckling, giggling and smiling haven't been studied yet—as part of a healthy lifestyle.

It's natural to wonder whether other mood interventions—such as psychotherapy and drugs—would benefit heart patients. Research is limited, but there's not much evidence that traditional one-on-one psychotherapy is beneficial. At least one study has shown a possible protective effect from antidepressants—but only from the SSRIs, a category that includes Zoloft, Paxil and Prozac. Other mood-altering drugs had no effect on heart disease, which suggests the benefits from SSRIs were a biochemical side effect, unrelated to depression as such.

For now, the state of the art in psycho-cardiology is the program developed by Dr. Dean Ornish.

Ornish's lifestyle regimen is best known for the stringency of its ultra-low-fat diet, but it places equal emphasis on exercise and stress reduction through yoga, meditation and support groups. Mel Lefer of Penngrove, Calif., credits it with saving his life. Lefer suffered a massive heart attack in 1985, when he was 53 years old. Overweight, a heavy smoker and a workaholic who ran three restaurants, he had also lost a son in an accident a few years earlier and had separated from his wife. Lefer's own cardiologist told Ornish not to bother enrolling him in a yearlong study because he would never live that long. Twenty years later Lefer is not just alive, but lean and energetic. And so is O'Connell, who joined an Ornish-based program at the Swedish American Health System in Rockford, Ill., after his second heart attack. Seven years have gone by since the day his doctors told him his case was hopeless.

It's ironic that psychological interventions—painless, risk-free and low-cost—are typically the treatment of last resort for heart patients who have exhausted all the possibilities of angioplasty, stents, bypass surgery and medication. "My favorite patients are those who have been told, 'There's nothing more we can do for you'," says Dr. Harvey Zarren, who runs an Ornish-inspired program at North Shore Medical Center's Union Hospital in Lynn, Mass. When he meets a new patient, he concedes that the medical options have been exhausted. Then he adds, "But here's what you can do for yourself." For two-and-a-half hours, one night a week, Zarren leads his patients in meditation, followed by yoga, relaxation exercises and a support-group session in which patients share their frustrations and accomplishments. In fact, Zarren does think there's more that medical science can do for most heart patients, but it doesn't involve fancier stents or new drugs. It's the investment of time and caring. One of the first questions he asks patients is, "With whom do you share your feelings?"

Someday that may be the model for treating heart patients: an approach that integrates lifestyle changes with a new outlook on life. It will involve a collaboration among cardiologist, nutritionist, psychologist, the patient and his family, bound together by the realization that the heart does not beat in isolation, nor does the mind brood alone.

© 2005 Newsweek, Inc.

~Joe

7 days left

"What do you mean I need open-heart surgery?" "What do you mean I had a stroke? "But I am under 40." Those were the words I was able to get out of my mouth...eventually. My hope is that this blog will help others who have similar experiences and need resources...JRS

Search This Blog

Friday, September 30, 2005

Thursday, September 29, 2005

Dedication

This post is dedicated to all those whom I consider close. You know who you are not just because you received an email from me addressing you as “Friends” but because of your reactions to my news.

I want you all to know that each email response, each hug, the shared stories of loved ones that went to the Cleveland Clinic or that had a similar surgery, the tears, the wishes for a speedy recovery, the philosophical conversations about faith and God, the hard lesson about what really matters, the jokes and levity, the look in your eyes, the offers to help whether it was to mow the lawn, bring over dinner, help Allison and Max or to pray; all of these things strengthen my resolve to go in fighting and come back stronger than ever.

Each and every one of you is amazing. I will take you all into the operating room with me and please know that I take great comfort in that.

~Joe

8 days left

I want you all to know that each email response, each hug, the shared stories of loved ones that went to the Cleveland Clinic or that had a similar surgery, the tears, the wishes for a speedy recovery, the philosophical conversations about faith and God, the hard lesson about what really matters, the jokes and levity, the look in your eyes, the offers to help whether it was to mow the lawn, bring over dinner, help Allison and Max or to pray; all of these things strengthen my resolve to go in fighting and come back stronger than ever.

Each and every one of you is amazing. I will take you all into the operating room with me and please know that I take great comfort in that.

~Joe

8 days left

What would you do?

In 9 days you’ll be having heart surgery. Not the “your arteries are clogged with sausage gristle and you bleed beef gravy” heart surgery, but the “you were born with an imperfection that you can blame on all the generations preceding you” heart surgery. You’re in better than average shape but running a few miles would have you breathing heavy. You don’t smoke, are relatively young and exercise at least 3 times a week though you’d be the first to admit that your intensity at the gym often matches that of your high school janitor’s enthusiasm for his job. So here is the question:

Do you get the cheeseburger?

Do you get the medium rare Neiman Ranch 1/3 pound, juicy beef burger with four strips of hickory smoked bacon, Wisconsin cheddar melting unevenly around the edge? The one with thick Bermuda onions, a slice of heirloom tomato that’s a deeper red than the ketchup and resting on a fluffy white bun dusted with flour?

Or…

Do you get the side salad?

Do you order the tasteless iceberg lettuce with julienned carrots, wrinkled cucumber slices and cherry tomatoes from a warehouse in Jersey City, NJ? Light ‘Italian’ dressing (on the side, of course).

The burger certainly won’t help matters, but when you’re looking at something like heart surgery, shouldn’t you try and enjoy every minute (and meal) you have? Because when I wake up, after the operation, I’m going to have a tube down my throat, IVs in my arm, a tube draining blood coming out of my chest, a catheter between my legs and a hang-over that you can really only get from having your ribs split open, your heart and lungs stopped and having a bunch of strangers playing Yahtzee inside your chest cavity for 4 hours. I won’t even have the appetite for those stupid F’ing cups of Jell-O that are found no where else but hospitals.

I’ll have the burger.

Hey, Dad, I understand now. I understand why a couple of years ago when your blood sugar was through the roof and you couldn’t get control of your blood pressure and you had to lose weight you said, “What’s the point of living if you can’t live?” And I’m sorry I was on you about eating healthier and losing weight. Don’t get me wrong, I’m glad you did, but I can truly empathize now.

Yes, I’m sure, I’ll have the cheeseburger. Does that come with fries?

~Joe

9 days left

Tuesday, September 27, 2005

The Joy of Doing Nothing

In today's world we rarely get the guilt free pass to do nothing. There are bills to pay, lawns to mow, emails to respond to, weddings to attend...laundry, dishes, org charts, authorizations, presentations, (insert other daily responsibilities here). But occassionally we intersect with times and life occurences which provide us with the opportunity to just say...."Sorry, the Dr. said I can't do that." What can I not do after the surgery?

- No lifting anything more than 10 lbs -- The good--I'm pretty sure the remote control is under 10lbs, The bad--Max weighs 11 lbs.

- No driving -- The good--No grocery shopping, The bad--The whole "Shut-In" thing doesn't suit me.

- No lifting my arms over my head -- The good --I can put off moving all of our junk from the basement to the attic a little bit longer, The bad--Button-up shirts severely limit your wardrobe options.

- No sleeping on my stomach -- The good-- it's supposed to be healthier for you, The bad--Obvioulsy it didn't prevent this situation...how good can it be?

- No exercise beyond very short walks -- The good--I'll finally meet the neighbors I've been avoiding. The bad -- I'll finally meet the neighbors I've been avoiding.

There have been two other times in my life when I wasn't able to do anything...Both those times were following knee reconstructions. I must say, for someone who is driven to constantly be busy or productive it is initially difficult to let go. But in some ways it is liberating to know that I just won't physically be able to do anything. It takes away any guilt associated with thinking that I should be creating, producing or checking off 'to-dos'. So I plan on taking full advantage...

- I'll sleep more (provided the pain meds work)

- I won't wear a watch

- I'll read some bad fiction rather than the latest business garbage put out by authors who have never been in the business world.

- I'll linger in bed with Allison, Max and super dog, Maggie without saying, "I've got to go." Few things will top this.

- I'll enjoy watching the leaves fall without the nagging feeling that I should be raking

- I won't apologize for watching Red Dawn on SpikeTV

- October is sports nirvana

~Joe

10 days left

Monday, September 26, 2005

The news.

How many of you have life insurance? It is the only thing you ever buy and hope you never use. But, as a guy who was bringing his first child into the world in a few months I wanted to do what was right...just in case. To me, it was just one more task I had to do before Max made his debut; really no different than painting his room.

The initial meeting with the agent at Northwest Mutual made it sound like it was just a formality. "Here's how much money you 'll get in 3o years...blah, blah, blah." Well, eight vials of blood....green light. 50 line questionnaire...green light. One Dixie cup of urine...green light. Two physicals with 2 different doctors who spoke broken English...green light. EKG while lying on the couch in my living room...green light. So I'm thinking, "OK, we're done here. Where do I sign?" "Well, Mr. Salvati, since you have a heart murmur, we'd like you to take one more test." "OK, what do you need to poke, prod, draw or monitor?" "Its a simple test...and echocardiogram (echo). It takes about 15 minutes.

The next day I arrive 5 minutes early for my appointment. Dr. Green at the Stamford Heart Associates has me lie down on the wax paper covering the table. Now this is an aside, but can someone tell me, with as much as medicine and technology have advanced over the years...have we still not come up with a better solution for sanitation in a Dr. office than the paper covering the table?

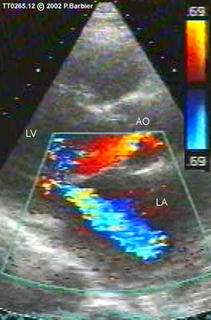

So, I'm sitting there, shirt off and we start the exam. I'm lying down on my back and Dr. Green takes a the "wand" and after applying some lubricating gel he applies the wand to my chest. A picture comes up in black and white on the screen and the Dr. begins pointing out parts of my heart. So now I'm thinking, "Cool. Give me the rubber stamp, Doc so I get back to work." But then he pauses in one area for a moment. Then, he flips a switch on the machine. The black and white switch to vivid colors. "The color is where your blood is moving. The brighter the color the more volume and thrust of the blood." So I'm seeing the colors and glancing at my watch. "So everything looks ok, Dr.?"

"Well, there are a couple of things that concern me."

Note to self. If I ever become a doctor, remove the word "concern" from my bedside vocabulary.

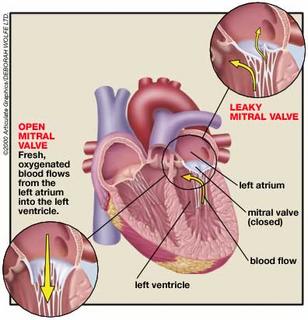

"Can you be more specific, Dr. Green" I ask. "Well, if you look at the bright colors, the whites, orange and reds, that's your blood." "And?" "Its going the wrong direction in your heart. The blood is traveling from your left atrium through your mitral valve and into your left ventricle. The problem is that that blood is regurgitating back into the left atrium. The result is that your heart is working not working efficiently. You have severe mitral valve regurgitation, Mr. Salvati. Your heart is growing and if we don't address this soon you'll be at in increased risk for heart attack, stroke or (my personal favorite) SUDDEN DEATH.

How do you digest this?

Denial: The Dr. doesn't know what he's talking about.

Fear: Never thought I would be checking mortality rates at 34.

Anger: Why me?

Acceptance: OK, let's find the best place and the best surgeon.

11 days to surgery

What is mitral valve regurgitation?

What is mitral valve regurgitation (MR)?

The mitral valve is similar to a one-way gate in the left side of your heart. Normally, the valve only allows blood to flow from the upper to lower heart chamber. But if the valve becomes diseased or injured so it cannot close properly, blood can leak backward (regurgitate) into the upper chamber (left atrium). This uncirculated blood causes the heart to work harder to pump the extra regurgitated blood (volume overload).

Mild cases of mitral valve regurgitation cause few problems, but more severe cases eventually weaken the heart and lead to heart failure.

See an illustration of the heart with its chambers and blood flow.

What causes mitral valve regurgitation?

There are two forms of mitral valve regurgitation: chronic and acute.

Chronic mitral valve regurgitation, the most common type, develops slowly over several years. The most common cause is mitral valve prolapse, in which the mitral valve flaps bulge the wrong way against the flow of blood, don't seal properly, and allow blood to leak backward. Other causes include heart failure, rheumatic fever, which can scar the heart valves, preventing them from closing completely; calcification of the tough ring of tissue (annulus) to which the mitral valve flaps are attached; congenital heart disease; and other heart problems.

Acute mitral valve regurgitation develops quickly and can be life-threatening. It occurs when the mitral valve or one of its supporting structures ruptures suddenly, creating an immediate overload of blood volume and blood pressure in the left side of the heart. Unlike chronic MR, your heart doesn't have time to compensate for the increased volume and pressure of blood. If not treated, acute MR can be fatal. Common causes of acute MR are heart attack and heart infection.

What are the symptoms?

If you have mild-to-moderate chronic mitral valve regurgitation, you may never develop symptoms. If you have moderate-to-severe disease, you may not have symptoms for decades. Depending on the severity of your mitral valve regurgitation and condition of your heart, you may not develop symptoms of heart failure until you're in your 40s, 50s, or 60s. Symptoms include shortness of breath with exertion, which later develops into shortness of breath at rest and at night; fatigue and weakness; and fluid buildup (edema) in the legs and feet.

With acute mitral valve regurgitation, you will be critically ill. Symptoms develop rapidly and include severe shortness of breath at rest, coughing, and rapid heartbeat.

How is mitral valve regurgitation diagnosed?

Most cases of mitral valve regurgitation are chronic and are diagnosed during a regular doctor's office visit. Acute mitral valve regurgitation is life-threatening and is usually diagnosed in the emergency room or while you are hospitalized.

Because you may not have symptoms with chronic mitral valve regurgitation, a specific type of heart murmur may be the first sign your doctor notices. Further tests will be needed to evaluate your heart and the severity of the regurgitation. Tests may include:

Various types of echocardiogram, a type of ultrasound to determine the severity of MR.

An electrocardiogram (EKG, ECG), to evaluate abnormal heart rhythms.

A chest X-ray, to evaluate heart size.

Cardiac catheterization, to determine the severity of MR and to look for coronary artery disease.

Tests for acute mitral valve regurgitation may include one or more of those used for chronic MR as well as a transesophageal echocardiogram, in which a device that sends sound waves is passed down the esophagus to take clearer images of the heart.

How is it treated?

Treatment for chronic mitral valve regurgitation includes monitoring your heart function and symptoms, preventing infection, and treating complications as they develop. Your doctor may prescribe medications, including: Vasodilators to help widen blood vessels and help the heart pump more efficiently.

Anticoagulants, such as warfarin (Coumadin), to prevent blood clots if you also have atrial fibrillation. Beta-blockers, or antiarrhythmics to control heart rate.

Antibiotics to prevent infections.

You may need surgery to repair or replace your mitral valve if the regurgitation becomes severe, if the size of your left ventricle (your heart's main pumping chamber) increases, or if your heart weakens. Mitral valve repair is preferred over replacement.

Treatment for acute mitral valve regurgitation occurs while you are hospitalized or in the emergency room. Because heart failure usually occurs with acute MR, vasodilators are given intravenously. Immediate surgery to repair or replace the valve will be necessary.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)